by Jason Tarnow | Jan 20, 2021 | Crime, Legal Rights, Police, Social Media, Wheels Of Justice

The internet is a precarious place. We buy, we sell, we talk – and we post. And while that’s all fine and good, it isn’t without consequence. Facebook launched in 2004, and since that time Canadian Courts have addressed and analyzed evidence obtained through Facebook and other social media platforms.

Recently, in a 2-1 decision, in R. v. Martin, 2021 NLCA 1, the Newfoundland and Labrador Court of Appeal overturned a lower court’s decision deeming Facebook screenshots as inadmissible. In a 30 page decision, the Court of Appeal explained how the Provincial Court Judge (“PCJ”) had erred in their analysis of the rules of authentication in relation to the proposed electronic evidence.

The case involves allegations that the Accused, Mr. E. Martin, made threats against the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary (police), via pictures and written communication on Facebook. He was charged with being in possession of a knife for a purpose dangerous to the public peace, being in possession of a rifle for a purpose dangerous to the public peace, and uttering a threat to members of the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary.

The police had attended Mr. Martin’s residence one evening to follow up on a domestic disturbance complaint. The investigation went no further than a brief attendance at the Accused’s residence, which resulted in no further action being taken.

The investigation with respect to the charges in this case began when the police received an anonymous tip that the Accused had posted several pictures on Facebook indicating he planned to harm police.

It was the evening following their first visit to Mr. Martin’s residence that the police received the anonymous tip that indicated he had posted a menacing caption, directed at police, combined with photos that included firearms. The police again attended Mr. Martin’s residence, but were clearly not welcomed. They returned to the detachment and tried to view Mr. Martin’s Facebook page, but were unable to view any content. The police then contacted the anonymous tipster to ask if they would email pictures of the postings, which they did. In total, six screen shots were forwarded. The “screenshots” depicted an individual in various poses, kneeling with and holding various firearms that included a rifle and a long gun. The words “Ed’s Post” and “Ed Martin added 4 new photos” appeared as “banners” over the photos, in the typical Facebook font and symbolism.

These screenshots were at the centre of the Crown’s firearms and threats charges against the Accused. A Voir Dire was held to determine the admissibility of the screen shots. Ultimately, the PCJ declined to admit the photos as evidence, reasoning that these items had failed to be authenticated. The PCJ opined that since the anonymous tipster had not been called to give evidence, no one could testify that the screenshots were not altered or changed in anyway. The Court went further to say that there had been nothing to substantiate that the Accused even had a Facebook account, and even if they did, there was no way to determine conclusively that the Accused had been the one to author the posts depicted in the screenshots.

The Accused was convicted of being in possession of a knife for a dangerous purpose (which was found on him at the time of his arrest) but was acquitted on the charges of being in possession of a rifle for a dangerous purpose to the public peace, and uttering a threat to members of the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary. The Crown appealed the PCJ’s decision to rule the screenshots inadmissible – which brings us to the Court of Appeal’s analysis of the issue.

The Court of Appeal was thorough and careful to reiterate its explanation of a key component in their analysis: the threshold for admissibility of authenticated electronic documents under the Canada Evidence Act is low, and can be established by both direct and secondary evidence. The proposed electronic evidence must be capable of supporting a finding that the evidence sought to be admitted is what it purports to be.

The Crown submitted that the PCJ had been erroneous in ruling that the screenshots were not authenticated by the evidence adduced at Trial. At the Voir Dire, 10 witnesses, all police officers, were called including the officer who began the investigation and obtained the screenshots. This police officer testified that he was very familiar with the layout of Facebook, and the screenshots were consistent with what he knows of Facebook. While not accepted by the PCJ as an acceptable form of authentication, the Court of Appeal disagreed and suggested that the officer’s testimony was evidence that the screenshots were authentic. Further, the police officer testified about identifying striking similarities between what they saw when they were in attendance at the Accused’s home – clothing, personal items, layout of the residence – that mirrored what they had seen in two of the screenshots. The Court of Appeal found that this information aided in the authentication of the screenshots, and determined that it was not necessary to have the anonymous tipster’s testimony verifying their authenticity. No evidence to the contrary was introduced by the Defence.

The Court of Appeal stressed that authenticity does not determine authorship – meaning that although the evidence is admissible, it is not determinative of who actually authored the post. As a result of their analysis, the Crown’s appeal was allowed and the case was returned back to Provincial Court for further proceedings. As is standard practice, the Court of Appeal did not comment on what probative value the evidence may have.

The introduction of digital evidence in criminal proceedings will continue to create a myriad of issues for the courts to determine. The Charter was not written with these intricacies in mind – and the responsibility lays not only with the courts, but in the hands of criminal lawyers across the country. If your case involves digital evidence (social media postings, text messages, etc.) it is imperative that you contact experienced and seasoned counsel without delay. We are licensed to practice in British Columbia, the Yukon Territory and the Northwest Territories.

by Jason Tarnow | Sep 2, 2020 | Crime, Criminal Attorney, Legal Rights, Media, Police, Politics, Social Media, Uncategorized

In one of our previous posts, we discussed biometric technology and the role it plays in Canadian law enforcement. It is, however, only one of the “predictive” tools utilized by the police in relation to criminal investigations.

A new report by the Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto goes into alarming detail regarding growth of algorithmic policing methods, and how this technology compromises the privacy rights of Canadian citizens. The report is incredibly thorough and comprehensive, delving into how this controversial technique offends various sections of our Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Firstly, though, it is important that our readers understand what algorithmic policing is.

The overall success of any algorithm is the system’s ability to gather, store, and analyze data – with law enforcement’s methodology being no different. A “location focused” algorithmic approach seeks to determine (predict) which areas are more likely to see criminal activity. The algorithmic system in these pursuits analyzes historical police data to identify geographical locations where crimes are, in theory, more likely to be committed. If this sounds familiar to you, then you’ve likely heard of, or accessed, the Vancouver Police Department’s GeoDash crime map – an online tool where you can navigate a map of the City of Vancouver by crime occurrence. You can choose from a variety of offences on the dropdown list, including homicide, break and enter, mischief, theft, and “offences against a person” which likely includes a variety of crimes such as sexual assault, assault causing bodily harm, and uttering threats. By looking at this map, you get an idea of which neighborhoods in Vancouver are most vulnerable to crime – except that it’s a little bit more sophisticated than that, and goes far beyond simply dropping a pin on the map. The public can see where the crime took place, but not who is alleged to have committed it. The offender’s personal information is logged, in as much detail as possible, and becomes part of a larger system dedicated to predictive surveillance – i.e., it creates a profile of which individuals are more likely to commit a particular crime. This profile can be used to identify people who are “more likely to be involved in potential criminal activity, or to assess an identified person for their purported risk of engaging in criminal activity in the future”.

While this information is definitely concerning, there is another issue: we have very little insight into the extent that this technology is being used. We know that the methods by which police gather information have historically discriminated against minority groups and those living in marginalized communities. This seems to guarantee that the VPD’s use of algorithmic investigative techniques relies on data that is often obtained through biased methods. We know that black and indigenous individuals are disproportionately represented in the correctional system, which can only mean that they are disproportionately represented in respect of these algorithms.

Although not everyone agrees that systemic racism exists within the VPD, the calls to address, unravel and mitigate the harm to marginalized groups continue to amplify. The idea that information collected under the apprehension of bias will not only remain on record, but will be used to further future investigations, is an indicator that Canadian law enforcement’s road to redemption will likely be a bumpy one.

by Jason Tarnow | Jul 2, 2020 | Crime, Criminal Attorney, Legal Rights, Media, Police, Riots, Social Media, Wheels Of Justice

Over the last couple of months, there has been outcry from the public urging the use of BWC’s (Body Worn Cameras) for Canadian law enforcement. Although initially in response to the growing unrest relating to police brutality in the United States, there are echoes of abandoned intentions from Canadian officials dating back at least a few years.

Back in 2015, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (“OPCC”) issued a publication regarding the use of BWC by police, in collaboration with privacy agencies in Alberta, New Brunswick and Quebec. The remaining Canadian law enforcement agencies from other provinces and territories acted “in consultation”.

For reference: according to the CBC, there were a total of 2 incidents involving the death of individuals at the hands of law enforcement in New Brunswick between 2012 and 2014, 12 incidents in Quebec, and 14 incidents in Alberta. Interestingly enough, British Columbia (on par with Quebec at 14 deaths) and Ontario (with the highest rate of police violence resulting in death in the country at 25 deaths between 2012 and 2014) were only acting in consultation.

The report hails the effectiveness of BWC to capture high quality images, videos, and audio recordings – so effective, in fact, that the OPCC had grave concerns regarding their ability to capture material that could jeopardize the privacy of innocent and uninvolved bystanders.

The report goes on to tout the value of BWC for evidentiary purposes, including analytics so sophisticated that the material obtained would likely be suitable for biometric comparison – aka, facial recognition.

There is no arguing the fact that the use of BWC by police has implications for the privacy of citizens in their everyday lives – especially since once fitted, citizens would likely expect on-duty officers to have their devices on a continuous basis as opposed to intermittently.

Benefits of BWC include the ability to review interactions between police and the public, recording communications between the police and suspects in the course of an investigation, identifying potential witnesses, and of course recording interactions between police officers. Many criminal cases involve evidence obtained through the use of dash cams, which provide audio from inside a police cruiser and video from the perspective of the driver. The effectiveness of this technology loses value when the investigation takes place outside of a police vehicle, as the audio often fails to capture intelligible communications between police and a suspect, or between officers themselves. Although the dash cam is kept running, the audio portion is often useless when the interactions between police and a suspect take place outside the vehicle, and the windows of the police cruiser are closed, or if the police/suspect leave the immediate area where the audio is successfully captured.

The report indicates that while continuous recording would undoubtedly provide a greater level of accountability for the actions of police, the threat to personal privacy reigns supreme:

“From an accountability perspective, continuous recording may be preferable because it captures an unedited recording of an officer’s actions and the officer cannot be accused of manipulating recordings for his or her own benefit. However, from a privacy perspective, collecting less or no personal information is always the preferred option”

In 2014, the Edmonton Police concluded a pilot project regarding the use of BWC by its officers. The conclusion?:

“The cameras had no effect on police use-of-force incidents and said there was no statistical difference in resolving police complaints”

According to an analysis done by CBC, there were a total of four deaths between 2012 and 2014 relating to officers of the Edmonton Police Service. By comparison, there were 9 deaths in the same period relating to officers of the Toronto Police Service. The results of the Pilot Project may have seen different results in a different jurisdiction.

The Edmonton Police explained that in addition to being ineffective to expose cases of police misconduct, the related expenses were simply unrealistic. Perhaps surprisingly, it’s not the cost of the devices themselves, but the expense to store and manage all of the material collected: somewhere between 6 and 15 million dollars over five years, which also includes hiring personnel qualified for the job.

Finding the balance between accountability, transparency and oversight of police against the protection of privacy for Canadian citizens is a legitimate and profound task – one that cannot be taken lightly. As the calls for BWC in Canadian law enforcement grow louder, and as Canadians revisit the reality of what it is to be privileged in this country, we can only hope that the values of dignity and equality are recognized as being more valuable than the cost of the equipment that very well could save lives.

by Jason Tarnow | Jun 23, 2020 | Crime, Legal Aid, Legal Rights, Media, Police, Politics, Riots, Social Media, Wheels Of Justice

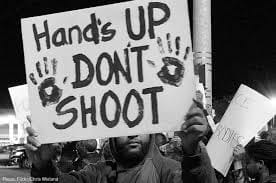

“Systemic racism is so rampant in the United States, I’m from Canada so I can’t even imagine what that must be like!”

“Police brutality in the US makes me proud to be Canadian”

The two statements above reflect a dangerous and widespread misconception held by many Canadians as they observe growing unrest in the United States:

“Deaths of minorities at the hands of law enforcement just isn’t an issue here”

Of course, nothing could be further from the truth.

Systemic racism exists in institutions across Canada – and an analysis of police brutality against minorities performed by CBC reveals some startling data.

Between 2000 and 2017, CBC was identified 461 fatal encounters between law enforcement and civilians. The RCMP– Canada’s largest and only federal police force – is responsible for the highest number of incidents at 118 casualties, followed by the Toronto Police Service at 52, and the Service de police de la Ville de Montreal at 32. The data demonstrates that these occurrences continue to rise steadily across the country.

When looking at the study, it is obvious that Caucasian individuals represent the largest number of victims per ethnic group, composing roughly 43% of all casualties identified. They also represent nearly 80% of Canada’s total population.

Indigenous victims represent roughly 16% of all casualties identified, but account for less than 5% of Canada’s total population.

Black victims represent roughly 10% of all casualties identified, but account for less than 3% of Canada’s total population.

22% of the victims were unable to be identified by ethnicity.

These facts are alarming and highlight a trend of violence by law enforcement against identifiable minorities. Aggravating circumstances further, it is estimated that mental health and substance abuse issues afflicted approximately 70% of the 461 victims.

The data further reveals that the majority of these occurred in urban areas with diverse cultural communities – not within areas densely populated by minorities. What this means is that of the percentage of the 461 fatalities that involve people of color is grossly disproportionate to the overall population of the areas affected.

Gun related deaths accounted for over 71% of the 461 fatalities, use of restraint at just shy of 16%, physical force at 1.3%, use of an intermediate weapon (a tool not designed to cause death with conventional use, such as a baton) at 1.1%, and “other” accounting for 10.1% of deaths.

Perhaps most shocking of all is that these statistics have not been compiled and presented by the organizations with the most reliable sources of information – the law enforcement agencies themselves.

The analysis conducted by CBC provides a glimpse into the systemic racism that is alive and well within law enforcement agencies across the country, but it hardly tells the entire story.

The data relates only to fatalities – it does not represent the wrongful arrests and prosecutions of minorities in Canada, the disproportionate sentences that are imposed, or the loss of dignity and liberty.

It does not represent the interactions that don’t result in an arrest or charges, nor does it represent the victims of racism and bias who will never have the opportunity to tell their stories.

by Jason Tarnow | May 20, 2020 | Crime, Criminal Attorney, Legal Aid, Legal Rights, Media, Police, Social Media, Wheels Of Justice

It goes without saying that the judicial system has been hit hard by COVID-19. This isn’t wildly surprising – there was no solid emergency response strategy in place for a situation like this, and as a result, a significant amount of time and resources have been expended to create a sense of control amongst the chaos.

It was acknowledged early on that certain individuals in the justice system would be disproportionately effected – accused persons in custody awaiting trial or sentencing, residents of remote communities that operate under a court circuit, and, of course, the victims in cases where there is uncertainty of if or when the case proceeds at all.

Since the World Health Organization declared a pandemic in response to COVID-19, law enforcement has tried to adapt where required. One of the most profound changes relates to the processing of newly accused individuals – and it may provide context into why intimate partner violence has surged during the pandemic. Between April 6 and May 6, 2020, 8 tragic incidents of domestic violence against women across Canada resulted in fatalities. There is, of course, no doubt about the fact that violence in relationships occurred before COVID-19, and will continue long after the pandemic is declared over – but there are aspects to a surge in intimate partner violence that are directly linked to the virus and to the policies that have been implemented when trying to process, manage, and supervise offenders.

Hundreds of accused persons awaiting trial in custody have been released, with chargeable offences ranging from assault, fraud, drug trafficking and beyond. Again, not surprising – as we’ve discussed previously on the blog, the correctional system serves as the perfect breeding ground for the virus, and it would be beyond cruel and unusual to take no action at all to protect those that are considered to be among the most vulnerable.

It’s the way that law enforcement has chosen to operate on a “catch and release” scheme in cases that would, under normal circumstances, require a bail hearing – and probably a highly contested one at that – that has likely contributed to domestic violence rates during COVID-19. Due to concerns about the nature of the virus and its ability to spread quickly, bail hearings have occurred less frequently, even with video-conferencing and telephone conferencing put into effect to streamline the process and protect the health of all parties involved. Instead of a bail hearing, an accused is more likely to be released on an Undertaking. The Undertaking may require that the accused check in with a bail supervisor weekly – something that is generally done on an in-person basis, where the most value lies in a face-to-face meeting – by telephone instead.

Aside from that, the “stay at home” order has, unintentionally, resulted in many victims of violence becoming prisoners in their homes. Public services like shelters and safe houses are stretched beyond capacity, and for some (especially people with underlying health conditions and people with children) entering into such an environment during a virus pandemic might seem even less tolerable than continuing to cohabitate with their abuser.

As with the other aspects of our lives – returning to work and school, chatting with our neighbors, planning vacations – the judicial system will, in one way or another, return to full operational capacity. But for those who have suffered the effects of intimate partner violence during the pandemic, there may be no return to the way things once were.