Mission Impossible: Managing COVID-19 in the Canadian Correctional System

On March 18, 2020, the BC court system responded to the coronavirus pandemic swiftly and without hesitation, reducing operations by the likes of which criminal counsel simply hasn’t seen before. Once it was confirmed how rapidly COVID19 spreads, the crowded confines of publicly accessed courtrooms were immediately deemed inappropriate – dangerous even. Since courtrooms often yield a congregation of some of society’s most vulnerable people, it made perfect sense to act defensively. These decisions, and many others effecting the justice system, were made only one week after the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic on March 11, 2020.

Unfortunately, there was a noticeable absence of urgency when it came time to protect the vulnerable inmate population overcrowded and totally confined within the walls of Mission Institution.

“In the worst-case scenario, CSC will need to order more body bags and find cold storage to stack up the bodies of those whose lives will be lost that could have been saved” – Justin Piche, criminologist, Criminalization and Punishment Project at the University of Ottawa

On March 31, 2020, federal Public Safety Minister Bill Blair recommended that the Correctional Service of Canada (“CSC”) immediately consider the release of non-violent inmates to mitigate the unavoidable reality that the virus could, and would, devastate the wellbeing of prison populations. His recommendation came on the heels of the CSC announcing the first two positive COVID-19 cases in federal institutions in Quebec.

On April 4, 2020, the CSC announced 4 confirmed cases at Mission Institution, leading to a lockdown of the facility.

By April 8, 2020, there were 11 confirmed cases, all inmates. Nearly one month had passed since the WHO declared a global pandemic.

By April 18, 60 inmates and 10 staff tested positive, and the CSC marked its first coronavirus related inmate death, exactly one month after the courts effectively shut down.

By April 25, 2020, 106 inmates and 12 correctional officers were confirmed to be infected, representing the largest outbreak in the Canadian Correctional System. On this date, the CSC advised that all inmates at Mission Medium Institution had been tested, but in any event, new cases were continuing to be discovered.

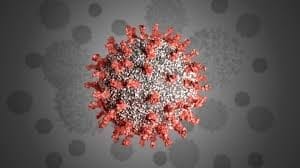

While disturbing, none of these developments are surprising. The largest incidence of outbreaks has been at long-term care homes – combining close quarters, limited mobility, and care-workers employed at more than one facility is a recipe for disaster when it comes to COVID-19, a pathogen that spreads and infects without discrimination. The same vulnerabilities exist within the correctional system, where they are intensified. Inmates and corrections staff are simply unable to practice crucial social distancing. Personal protective equipment for inmates has not been prioritized as it has in other sectors, despite these individuals being at a much higher risk of getting sick.

The CSC responded to COVID-19 by prohibiting visits to inmates, temporary absences, work releases, and inmate transfers between correctional facilities. While these steps likely helped to curb the spread of the virus, as a whole, they are grossly inadequate. Without a vaccine, social distancing remains our greatest defence against the virus. For the inmates at Mission Institution and those incarcerated at facilities across Canada, proper protective equipment is hard to come by, but hope is even harder.