by Jason Tarnow | Sep 28, 2020 | Crime, Legal Aid, Legal Rights, Media, Politics, Social Media, Wheels Of Justice

Section 2 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms grants all Canadians the fundamental right of freedom of expression – but as one young man in Markham, Ontario learned this week, the Charter also permits the enforceme nt of reasonable limits on expression.

nt of reasonable limits on expression.

18 year old Tristan Stronach, a grade 12 student, was charged under section 372(2) of the Criminal Code – making indecent communications – after his instructor had to conclude an online lesson after Stronach allegedly made racist remarks about the black community. The nature of the alleged comments, while not described specifically, has caused some to ask: why isn’t he being charged with a hate crime?

The answer is: because there is no specific “hate crime” offence in the Criminal Code.

Section 372(2) of the Criminal Code reads as follows:

Indecent communications

(2) Everyone commits an offence who, with intent to alarm or annoy a person, makes an indecent communication to that person or to any other person by a means of telecommunication.

“But what about hate speech?”

Section 319(1) of the Criminal Code reads as follows:

Public incitement of hatred

319 (1) Everyone who, by communicating statements in any public place, incites hatred against any identifiable group where such incitement is likely to lead to a breach of the peace is guilty of:

(a) an indictable offence and is liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years; or

(b) an offence punishable on summary conviction.

Wilful promotion of hatred

(2) Everyone who, by communicating statements, other than in private conversation, wilfully promotes hatred against any identifiable group is guilty of

(a) an indictable offence and is liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years; or

(b) an offence punishable on summary conviction.

While it has been made clear that the allegations relate to racist comments towards a single identifiable group – the black community – charges under this section were likely not approved because the evidence is unable to support a conviction. The comments were not made in a “public” place, and while they were made in the virtual presence of a group of individuals, they did not promote hatred – i.e., the comments weren’t made in such a way that they would result in other individuals following suit and creating a breach of the peace as a result.

Notwithstanding the above, if the accused is convicted of making indecent communications, the court will consider to what degree bias, prejudice, or hate played a role. These are aggravating factors that could result in a harsher sentence. Through this legislative structure, these aggravating factors can be considered for a variety of offences – assault, theft, murder, and so on.

As Canadians, we are very fortunate to live in a country that allows us to speak, move, and exist freely – but cases like this are a reminder that equality reigns supreme.

by Jason Tarnow | Sep 2, 2020 | Crime, Criminal Attorney, Legal Rights, Media, Police, Politics, Social Media, Uncategorized

In one of our previous posts, we discussed biometric technology and the role it plays in Canadian law enforcement. It is, however, only one of the “predictive” tools utilized by the police in relation to criminal investigations.

A new report by the Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto goes into alarming detail regarding growth of algorithmic policing methods, and how this technology compromises the privacy rights of Canadian citizens. The report is incredibly thorough and comprehensive, delving into how this controversial technique offends various sections of our Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Firstly, though, it is important that our readers understand what algorithmic policing is.

The overall success of any algorithm is the system’s ability to gather, store, and analyze data – with law enforcement’s methodology being no different. A “location focused” algorithmic approach seeks to determine (predict) which areas are more likely to see criminal activity. The algorithmic system in these pursuits analyzes historical police data to identify geographical locations where crimes are, in theory, more likely to be committed. If this sounds familiar to you, then you’ve likely heard of, or accessed, the Vancouver Police Department’s GeoDash crime map – an online tool where you can navigate a map of the City of Vancouver by crime occurrence. You can choose from a variety of offences on the dropdown list, including homicide, break and enter, mischief, theft, and “offences against a person” which likely includes a variety of crimes such as sexual assault, assault causing bodily harm, and uttering threats. By looking at this map, you get an idea of which neighborhoods in Vancouver are most vulnerable to crime – except that it’s a little bit more sophisticated than that, and goes far beyond simply dropping a pin on the map. The public can see where the crime took place, but not who is alleged to have committed it. The offender’s personal information is logged, in as much detail as possible, and becomes part of a larger system dedicated to predictive surveillance – i.e., it creates a profile of which individuals are more likely to commit a particular crime. This profile can be used to identify people who are “more likely to be involved in potential criminal activity, or to assess an identified person for their purported risk of engaging in criminal activity in the future”.

While this information is definitely concerning, there is another issue: we have very little insight into the extent that this technology is being used. We know that the methods by which police gather information have historically discriminated against minority groups and those living in marginalized communities. This seems to guarantee that the VPD’s use of algorithmic investigative techniques relies on data that is often obtained through biased methods. We know that black and indigenous individuals are disproportionately represented in the correctional system, which can only mean that they are disproportionately represented in respect of these algorithms.

Although not everyone agrees that systemic racism exists within the VPD, the calls to address, unravel and mitigate the harm to marginalized groups continue to amplify. The idea that information collected under the apprehension of bias will not only remain on record, but will be used to further future investigations, is an indicator that Canadian law enforcement’s road to redemption will likely be a bumpy one.

by Jason Tarnow | Jun 23, 2020 | Crime, Legal Aid, Legal Rights, Media, Police, Politics, Riots, Social Media, Wheels Of Justice

“Systemic racism is so rampant in the United States, I’m from Canada so I can’t even imagine what that must be like!”

“Police brutality in the US makes me proud to be Canadian”

The two statements above reflect a dangerous and widespread misconception held by many Canadians as they observe growing unrest in the United States:

“Deaths of minorities at the hands of law enforcement just isn’t an issue here”

Of course, nothing could be further from the truth.

Systemic racism exists in institutions across Canada – and an analysis of police brutality against minorities performed by CBC reveals some startling data.

Between 2000 and 2017, CBC was identified 461 fatal encounters between law enforcement and civilians. The RCMP– Canada’s largest and only federal police force – is responsible for the highest number of incidents at 118 casualties, followed by the Toronto Police Service at 52, and the Service de police de la Ville de Montreal at 32. The data demonstrates that these occurrences continue to rise steadily across the country.

When looking at the study, it is obvious that Caucasian individuals represent the largest number of victims per ethnic group, composing roughly 43% of all casualties identified. They also represent nearly 80% of Canada’s total population.

Indigenous victims represent roughly 16% of all casualties identified, but account for less than 5% of Canada’s total population.

Black victims represent roughly 10% of all casualties identified, but account for less than 3% of Canada’s total population.

22% of the victims were unable to be identified by ethnicity.

These facts are alarming and highlight a trend of violence by law enforcement against identifiable minorities. Aggravating circumstances further, it is estimated that mental health and substance abuse issues afflicted approximately 70% of the 461 victims.

The data further reveals that the majority of these occurred in urban areas with diverse cultural communities – not within areas densely populated by minorities. What this means is that of the percentage of the 461 fatalities that involve people of color is grossly disproportionate to the overall population of the areas affected.

Gun related deaths accounted for over 71% of the 461 fatalities, use of restraint at just shy of 16%, physical force at 1.3%, use of an intermediate weapon (a tool not designed to cause death with conventional use, such as a baton) at 1.1%, and “other” accounting for 10.1% of deaths.

Perhaps most shocking of all is that these statistics have not been compiled and presented by the organizations with the most reliable sources of information – the law enforcement agencies themselves.

The analysis conducted by CBC provides a glimpse into the systemic racism that is alive and well within law enforcement agencies across the country, but it hardly tells the entire story.

The data relates only to fatalities – it does not represent the wrongful arrests and prosecutions of minorities in Canada, the disproportionate sentences that are imposed, or the loss of dignity and liberty.

It does not represent the interactions that don’t result in an arrest or charges, nor does it represent the victims of racism and bias who will never have the opportunity to tell their stories.

by Jason Tarnow | May 12, 2020 | Crime, Criminal Attorney, Legal Aid, Legal Rights, Media, Riots, Social Media

On March 18, 2020, the BC court system responded to the coronavirus pandemic swiftly and without hesitation, reducing operations by the likes of which criminal counsel simply hasn’t seen before. Once it was confirmed how rapidly COVID19 spreads, the crowded confines of publicly accessed courtrooms were immediately deemed inappropriate – dangerous even. Since courtrooms often yield a congregation of some of society’s most vulnerable people, it made perfect sense to act defensively. These decisions, and many others effecting the justice system, were made only one week after the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic on March 11, 2020.

Unfortunately, there was a noticeable absence of urgency when it came time to protect the vulnerable inmate population overcrowded and totally confined within the walls of Mission Institution.

“In the worst-case scenario, CSC will need to order more body bags and find cold storage to stack up the bodies of those whose lives will be lost that could have been saved” – Justin Piche, criminologist, Criminalization and Punishment Project at the University of Ottawa

On March 31, 2020, federal Public Safety Minister Bill Blair recommended that the Correctional Service of Canada (“CSC”) immediately consider the release of non-violent inmates to mitigate the unavoidable reality that the virus could, and would, devastate the wellbeing of prison populations. His recommendation came on the heels of the CSC announcing the first two positive COVID-19 cases in federal institutions in Quebec.

On April 4, 2020, the CSC announced 4 confirmed cases at Mission Institution, leading to a lockdown of the facility.

By April 8, 2020, there were 11 confirmed cases, all inmates. Nearly one month had passed since the WHO declared a global pandemic.

By April 18, 60 inmates and 10 staff tested positive, and the CSC marked its first coronavirus related inmate death, exactly one month after the courts effectively shut down.

By April 25, 2020, 106 inmates and 12 correctional officers were confirmed to be infected, representing the largest outbreak in the Canadian Correctional System. On this date, the CSC advised that all inmates at Mission Medium Institution had been tested, but in any event, new cases were continuing to be discovered.

While disturbing, none of these developments are surprising. The largest incidence of outbreaks has been at long-term care homes – combining close quarters, limited mobility, and care-workers employed at more than one facility is a recipe for disaster when it comes to COVID-19, a pathogen that spreads and infects without discrimination. The same vulnerabilities exist within the correctional system, where they are intensified. Inmates and corrections staff are simply unable to practice crucial social distancing. Personal protective equipment for inmates has not been prioritized as it has in other sectors, despite these individuals being at a much higher risk of getting sick.

The CSC responded to COVID-19 by prohibiting visits to inmates, temporary absences, work releases, and inmate transfers between correctional facilities. While these steps likely helped to curb the spread of the virus, as a whole, they are grossly inadequate. Without a vaccine, social distancing remains our greatest defence against the virus. For the inmates at Mission Institution and those incarcerated at facilities across Canada, proper protective equipment is hard to come by, but hope is even harder.

by Jason Tarnow | Feb 11, 2020 | Crime, Criminal Attorney, Media, Police, Riots, Social Media, Wheels Of Justice

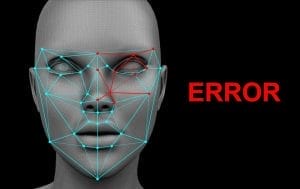

“Not only is this a concern with the possibility of misidentifying someone and leading to wrongful convictions, it can also be very damaging to our society by being abused by law enforcement for things like constant surveillance of the public”

– Nicole Martin, Forbes contributor

Star Trek. Back to the Future. District 9. I, Robot. These are only a few examples of films that have relied on biometrics – more commonly referred to as Facial Recognition – as a theme for entertainment. All are fiction based and while you may have thought of biometrics as a tool used by elusive government agencies like the FBI and CIA, that isn’t the case at all. Advancements in biometric technology have been seized upon by various law enforcement and government agencies across Canada – creating serious concerns from privacy and civil liberty advocates, and of course, criminal defence counsel.

The Calgary Police Service began using Facial Recognition technology in 2014. The system they use, known as NeoFace Reveal, works by analyzing an uploaded image and translating it into a mathematical pattern known as an algorithm. The image is then logged in a database and used for comparison against other uploaded images.

The Toronto Police Service hopped on board too. They reported uploading 800,000 images into their Repository for Integrated Criminalistic Imaging, or RICI by 2018. Their use of biometrics began with a trial in 2014, and in 2018, the Service purchased a system at a cost of about $450,000. Between March and December of 2018, the Toronto Police Service ran 1,516 searches, with about 910 of those searches (or 60%) resulting in a potential match. Of those potential matches, approximately 728 people were identified (about 80%). There were no statistics provided in relation to ethnicity, age, or gender, however, research has raised concerns about disproportionate effects of biometrics as it relates to people of color.

Manitoba Police do not currently use biometric technology as an investigative tool, although the idea was floated around in 2019 after the commission of a report concerning growing crime rates in Winnipeg’s downtown core. The Provincial government in Manitoba went so far as to suggest that this technology could be used to identify violent behavior – which sounds a lot like active surveillance, an unethical use of biometrics, which demonstrates one of the most profound concerns surrounding use of this technology. And while it is only a matter of time until the Manitoba Police do use this technology, many retailers in the province are already using it.

At home here in British Columbia, the Vancouver Police Department denies using Facial Recognition technology as a mechanism to investigate crime – in fact, back in 2011, they turned down ICBC’s offer to assist in identifying suspects involved in the Vancouver Stanley Cup Riots with the aid of their software. The office of the BC Privacy Commissioner confirmed that any use of ICBC’s facial recognition data by the VPD would amount to a breach of privacy for its customers.The office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada has been keeping track since at least 2013 – yet, there is little regulation of the use of biometrics in public and private sectors.

The same cannot be said for the RCMP in British Columbia, who, as recently as two weeks ago refused to confirm or deny use of biometrics as an investigative tool, but questions have been raised as to whether or not the RCMP is a client of Clearview AI, a facial recognition startup pioneered by US citizen Hoan Ton-That. Clearview’s work has not gone unnoticed – Facebook and Twitter have issued cease and desist letters, making it very clear that they do not support Clearview’s objectives. Google issued a cease and desist letter as well – however, their position on biometrics is fuzzy – especially since they are trying to make advancements in this area as well. So far, though, they have come under fire for their tactics and the results that have been generated.

The Canadian Government’s position on the use of biometrics is established on their website. When you submit your biometric information at Service Canada (for example), your information isn’t actually stored there, rather, it is sent to the Canadian Immigration Biometric Identification System, where it will remain for a period of 10 years. Further, your biometrics information will be shared with the United States, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. And yes – you can refuse to provide this information – but it will likely put a kink in your travel plans.

One important factor to consider about all of these agencies and their use of biometric technology is that this tool was never intended for use as active surveillance, or a method to intervene in incidents of crime in real-time. Whether it is a violent assault, sexual assault, theft under or over $5,000, murder or kidnapping, biometrics is an “after the fact” investigative mechanism. If used ethically and within parameters that preserve the privacy of all citizens 100% of the time, perhaps there would be no need for alarm – but that is incredibly unlikely. As more agencies begin to use this technology, the lack of regulatory oversight is bound to create an enormous pervasion of your privacy – and you may never know about it.

nt of reasonable limits on expression.

nt of reasonable limits on expression.